Geopolitics of 5G and 5G-Connected Massive & Critical IoT

Emerging Technology and Geopolitics of 5G

There are several reasons emerging technology is a highly competitive industry, notwithstanding the race for intellectual property that can be licensed by burgeoning markets for revenue. A first-mover advantage is often a way to lock in relationships that can lead to long-term infrastructure commitments, integration support services, and service delivery platform development. As the adage goes, “Whoever owns the platform, owns the customer.” This race to be the first to establish technological platforms and lock-in their customers is increasingly becoming politicized. And 5G, the next generation of cellular mobile communications technology, is the best example of how geopolitics is getting involved in emerging tech decisions and how technology discussions are influencing geopolitics.

The potential economic gains from 5G development and deployment, the civilization’s likely future dependence on 5G, and 5G’s potential use for military applications make it a prime candidate for political influence. Indeed, we can already see many governments’ involvement in 5G standards development, the decisions about spectrum allocation and auctions, and regulations to protect these next-gen mobile data networks from cyber threats. Even the location of the 5G supply chain participants can be a point of contention in negotiations within the political realm. This, most recently, governments have begun scrutinizing the vendors who manufacture the 5G infrastructure and devices to establish who would be permitted to sell this technology within certain countries. Never before have we seen such extensive global government involvement in emerging technology platform decisions.

Recent events like the U.S. attempts to influence banning of Huawei gear in various countries, the growing policy debate about 5G, and the inflamed political rhetoric regarding 5G technological independence are somewhat reminiscent of the energy independence issue – a topic that, over the last few decades, has shaped trade and foreign policy, and, to an extent, international armed conflicts.

Is all this political attention on 5G warranted? How critical could 5G first-mover advantage be while 4G is still being rolled out in many parts of the world? Why is the technological independence and technological superiority in the next generation of mobile communications becoming a matter of extraordinary national concern? Why is a single technology starting to influence geopolitics? Why now?

Why now? – The Decade of 5G Roll-out Is Kicking off Now

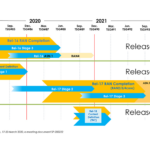

Before addressing the “why”, we should understand that the 5G roll-out is not going to be a fast process. While wireless carriers around the world are currently on the verge of transitioning to 5G, the roll-out of 5G networks is expected to take at least 10 years to complete. This means that current and near-term country-level decisions regarding 5G partnerships will have consequences for companies and economies for decades to come.

According to the GSMA trade group, about 1.2 billion people – 460 million in China alone – will have access to 5G networks by 2025. The pace of network implementation will only increase after that. As a result, the specific pace of 5G deployment for each country will depend on a variety of factors, including:

- Governments’ regulatory requirements;

- The costs, availability, and scalability of 5G infrastructure in a given country;

- The identification of compelling use cases and high-value applications for 5G networks;

- Mobile network operator technical and business model preferences;

- Infrastructure- and equipment-maker product timelines and roadmaps; and

- The ability for various players to capture value in a complex technology ecosystem.

For some countries a full roll-out alone might take decades. Even those that at the leading edge of implementation are planning on working with 5G technologies for decades to come believing that hat the next few generations of communication technologies will be only minor improvements to 5G rather than another step change.

If such predictions are true, decisions regarding the 5G technology with potentially very long-term consequences have to made now regardless of what the status of current implementation is. And the stakes are high. Should a country fall behind in 5G implementation, or not secure their implementations adequately, it might negatively impact their ability to survive and thrive in its daily operations, trade, and military endeavors.

How can 5G Influence the Stability, Economy and Security of a Nation and Geopolitics between Nations

Due to the potentially significant impact 5G can have on civilization’s functioning, decisions related to 5G technology cannot be made solely in the realm of business, as its application and implementation also hold considerable political consequences. From a purely technological and business perspective, the ideal would be for tech companies to first-movers in the development and roll-out of 5G to make decisions. Yet, many governments, particularly in Europe and the U.S., have entered into a political debate surrounding the technology by highlighting concerns that can lead to delays in such business-related initiatives. As a result, 5G is becoming an increasingly hot-button political issue.

5G as a Catalyst for Innovation and Economic Growth

The ability to commercialize a technology first is highly correlated to the bulk of related revenues. This greenfield approach for early and successful deployments delivers long-term benefits to those first-placed companies, and, consequently, significant economic gain for their home countries.

A January 2019 report to the U.S. Congressional Leadership highlighted that 5G and its related applications attract both talent and capital. The report states that the deployment of 5G is likely to, “…support 22 million jobs by 2035,” and, “…could generate US$12.3 trillion in sales activity across multiple industries.” Additionally, a presentation submitted to the U.S. House of Representatives suggests that a 5G superhighway could further impact the country’s GDP by +3%, while GSMA calculates that China’s 5G mobile ecosystem will be equivalent to 5.5% of China’s overall GDP. A European Commission supported study also estimates that a €56.6 billion investment in 5G by 2020 could create 2.3 million jobs in Europe and economic benefits of €113.1 billion per year by 2025.

A unique aspect of 5G that sets it apart from earlier mobile network generations is that it not only boosts the mobile device experience but introduced network capabilities for new classes of connected devices and industrial applications, including Massive Internet of Things (mIoT) and Critical IoT, autonomous transportation, and smart cities. Each of these new applications can generate massive datasets over 5G that can, in turn, demand advanced analytics and further stimulate innovation. Industrial scale deployments of mIoT are also likely to enable other new vectors for innovation.

Thus, 5G’s potential for significant economic impact post-2020 makes it a topic of worldwide importance, especially in respect to how the ability to quickly and effectively implement the technology in a country might affect a country’s global socioeconomic standing. 5G application, or delay therein, could lead to shifts in the current socioeconomic power dynamics, and no country wants to be left behind.

5G as the Most Critical of Critical Infrastructures

The focus of previous generations of mobile data networks has been on consumer voice and data services. With the introduction of high-speed, low-latency, and low-power 5G applications, such as IoT, new types of machine-to-machine (M2M) communication will be possible. As society adopts 5G-enabled mIoT, the number of devices on the network are likely to explode. These devices could include traditional mobile and broadband connections, as well as many other types of connected devices ranging from advanced medical equipment and safety systems to autonomous and connected transport systems and power plants.

It is predicted that, in time, users will start adopting 5G to connect all infrastructure upon which civilization relies. When this occurs, the technology will rapidly become part of each country’s critical national infrastructure, as well as a core capability on which every other critical national infrastructure sector will depend on.

While the current debate is often framed as a privacy and a counter-espionage concern, more important risks related to 5G are cyber-kinetic in nature. The consequences of 5G being sabotaged, or being used to sabotage the critical infrastructure connected to it are significantly more serious than the posed privacy concerns, as such attacks might directly impact the physical well-being and lives of citizens or the environment.

Based on such assertions, it is clear that winning a war without a single shot may become a prospect for those who can take over the control of their adversary’s 5G networks. It is critical, therefore, that the importance of, and increased reliance on 5G over time becomes wholly understood and solidified. This is particularly true with the regard to envisioning the plausibility of a time in the not-so-distant future where the criticality and security of 5G will need to surpass other critical infrastructure sectors in order to ensure the safety and security of global citizens.

5G as an Enabler of the Future of Warfare

While cybersecurity and intelligence-gathering questions are the present focus of the 5G debate, some current and aspiring superpowers see the potential that 5G technologies bring to their respective military forces and are already moving some of their military communications to a wireless, mobile, and cloud-based systems built around 5G technology.

The ability to transmit more data, achieve better network responsiveness through lower network latency, and reduce energy consumption, as is possible over 5G networks, can enable mission-transforming machine-to-machine communications over 5G. Such communication can be incredibly useful for military-related endeavors. For example, sensors from multiple locations can be used to generate a unified picture of the battlefield. Small teams can be deployed with encrypted group communications while providing visibility to command and control. 5G-enabled access to the abundance of computation could enable Artificial Intelligence (AI) support for every aspect of a mission. Low motion-to-photon latency with 5G-enabled mobile/wireless virtual reality (VR), mixed reality (MR), and augmented reality (AR) that could make soldiers that much more effective. And even now, lethal autonomous weapon systems, such as “killer” drones, micro-drones, drone swarms and other types of autonomous military robots are already being tested.

However, while such military-related technological abilities are in consideration at present, they are unlikely to be early use cases of 5G technology. That is, 5G’s application for large scale military endeavors are not likely to occur until the jamming of 5G signals and the technology’s growing cybersecurity vulnerabilities are mitigated.

Why Is One Company – Huawei – at the Center of Political Concerns?

5G for mobile devices relies on the evolving capabilities of current 4G technologies. However, as we have seen throughout the presentation of political concerns surrounding the technology, preparing for new use cases and applications of 5G must take on a next-gen network (NGN) approach that is more heavily influenced by political concerns.

This NGN approach means that the base stations and related systems (i.e. all 5G infrastructure) form the key battlegrounds. Currently, three core infrastructure providers exist for 5G: Sweden’s Ericsson, China’s Huawei, and Finland’s Nokia. While all three have shown 5G capabilities that conform to international standards, China’s Huawei remains the only one able to produce the most complete commercially-available solution to network carriers today. It has already built up such a strong lead that it is practically irreplaceable for many carriers that want to be among the first to offer the new services.

As BT’s Chief Architect recently stated: “…there is currently only one provider of 5G gear and that’s Huawei.” So, without partnering with Huawei, the 5G deployment gap for companies and countries will become even larger. Partnering with Ericsson or Nokia might have been a viable alternative at first, but it requires markets to wait for standalone 5G deployments; a clear competitive disadvantage in the telco world when compared to immediacy available through Huawei.

From a mobile network operator perspective, another unique advantage of working with Huawei is that the company, more than its competitors, is willing to innovate, iterate, and customize per carrier.

Many telcos around the world are also already chock-full of older, but still necessary, Huawei equipment, which might not be compatible with Huawei’s competitors’ 5G gear. Should a company then opt for non-Huawei 5G implementation, they face far greater expenses. So, it’s a big “ask” from telcos not to work with Huawei … at least for the moment.

Yet, that’s exactly what the U.S. and its allies are increasingly asking from their telcos through their vocal opposition to Huawei’s advanced market position. Leading the cries of countries’ claims of risks to critical national infrastructure through the use of Huawei-supplied 5G gear are fears of the enabling of intelligence-gathering opportunities and/or the introduction of sabotage vulnerabilities through the supplier’s “backdoors”. To support such claims, the U.S. government highlights Article 7 of China’s National Intelligence Law, passed in 2017, that states that organizations and citizens must, “support, co-operate with and collaborate in national intelligence work” as the key evidence to the Huawei risk.

And intelligence-related risks are not a new concern either. A 2012 Investigative Report on the U.S. National Security Issues Posed by Chinese Telecommunications Companies Huawei and ZTE shows that the Chinese telecom duo have remained a topic of interest within U.S. politicians for many years. The U.S. and other countries have also already placed restrictions on procurement of Chinese network equipment for core government and commercial data networks. The introduction of 5G has further increased such security concerns, and Huawei (and its parent nation), as the frontrunner, bears the brunt of the backlash.

How Real Is the Chinese Economic, Political and Military Threat?

While Western governments used to think of 5G as an important but incremental evolution of existing telecommunications services, China has positioned 5G as the central element of its economic and military power for the 21st century. The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the country’s US$1 trillion global infrastructure development and investment strategy, goes hand-in-hand with technology enterprises, such as the deployment of 5G telecommunications infrastructure within countries associated with the Initiative. The BRI also means the replacement of the U.S.-controlled Global Positioning System (GPS) with the Beidou precision navigation and timing system; the development of Global Energy Interconnection – a massive global electricity grid powered by renewable sources; and strategic investment in AI and IoT. Add to this the increased deployment of forward air and naval installations for China’s armed forces in countries like Djibouti, Sri Lanka and Pakistan, and the Chinese plan to rise to global “superpowerdom” starts to take shape.

The pursuit of 5G in China was set in motion by its government in 2015 with its state-led Internet+ plan. This initial plan was followed by the 13th Five Year Plan in 2016. These initiatives went beyond individual business interests by aligning government, university research, and Chinese industries with a singular 5G objective.

China has outsmarted and outplayed the U.S. by focusing on the development of advanced technologies over raw military power. No wonder, then, that the U.S. is panicking. In January 2018, the National Security Council (NSC) produced the presentation Secure 5G: The Eisenhower National Highway System for the Information Age that includes a dire warning: In the race to 5G, the U.S. is losing to China – if that doesn’t change, China will win politically, economically, and militarily.

Huawei’s Politically-backed and China’s Technologically-backed Advantage

The focus of China in the fundamental development, advancement, and promotion of 5G tech has clearly established this country’s advantage over players like those in the U.S. and Europe. Indeed, both China as a country, and its leading 5G tech company, Huawei, enjoy various advantages that reflect the country’s 5G commitment and investment in innovation. In past decades, China was portrayed as an intellectual property (IP) thief. It quickly emulated or copied ideas from outside the country to become a “fast follower”. However, in recent years, it has transformed into an innovation powerhouse. Western-educated Chinese scientists have returned to their homeland in numbers, and there is now centrally-funded innovation. Further advantages can be seen in how:

- Market analysts suggest that there are several times more AI start-ups funded in Shenzhen alone (China’s original Economic Zone near the border of Hong Kong) compared to the U.S.’s Silicon Valley;

- China has invested over US$500 billion in smart grid development compared to ~US$12 billion in the U.S.; and

- IoT and 5G are driven by the Chinese government as strategic imperatives.

China also has a unique cultural approach to solving challenges by using its large population and workforce to achieve change. For example:

- Huawei has 10,000 PhDs on staff;

- The adoption of IoT and 5G use cases is faster than in other nations also due to a large initial user base in China;

- Citizens are used to surveillance, resulting in no (significant) new privacy concerns; and

- The rapid growth of China’s middle class, and tech-savvy younger generations entering the workforce, has led to a greater population who are willing to adopt new technology like mobile app payments in place of paper currency or credit cards for transactions.

Through the BRI initiative and Chinese financial globalization (or, as some China skeptics call it – “financial imperialism”), Huawei’s 5G is poised to expand throughout Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America. It is also likely that, through their currently advanced technical capabilities, Huawei will even capture a significant market share even in the West.

From the perspective of the U.S. the Chinese threat is as real as it gets. Even without “backdoors”, risks to U.S. global technological, economic, and even military supremacy are significant, as China and Huawei continue capturing more of the market share.

How is the U.S. Fighting China’s 5G Threat?

In order to understand how the U.S. is fighting the technological encroachment from China, and why the 5G commercial conflict is a sign of changing times, we need to see the background of the situation. In the last decade or so, the U.S. has increasingly seen China as an adversary in world politics. Unlike the European Union, which shares democratic and liberal values with the U.S., China appears more alien and, thus, in some sense more dangerous to the U.S.’s interests and ideas on how the world should be run. From Obama’s pivot, to sanctions and Trump’s trade war that is far from being a Trump-only supported policy, the U.S. has found itself in increasing contention with China. Whilst the situation is very far from any physical conflict, the two have been competing politically, geographically, and commercially for years.

Right now, the main way in which the U.S. is fighting China’s encroachment is by attempting to maintain the current standards and norms of international diplomacy and business that are similar to its own ideals of democracy and capitalism. This means that various conflicts have arisen within the World Trade Organization (WTO) when shifts away from such norms are perceived. Furthermore, manoeuvrings within various international organisations that were initially established by Western ideals and nations, including the World Bank and the UN, have occurred. This has had mixed effectiveness, as China has, to some extent, successfully responded by creating its own alternative institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the aforementioned BRI initiative that seeks to further connect Asia with Europe and tempt Europe towards greater neutrality.

We see a lot of these U.S. defensive trends coming to fruition within the 5G arena. Essentially, Huawei and China have become fully-empowered infrastructure-tier technological platform competitors. Whilst, in prior situations, such technological advancements would have been exclusively Western inventions (consider such technological developments as computers, GPS, Windows, Android, and so on), in the case of 5G, China is ahead this time. Now that the competitive edge is in the hands of China, the U.S. feels the need to employ political as opposed to commercial capabilities in order to ensure that China does not gain more ground on what has traditionally been a U.S./European function in the world economy.

The primary outworking of the U.S.’s “norms maintenance” strategy has been its gambit to have Huawei banned in as many markets as possible, based on claims of “backdoor” risks associated with the company and its technology. Indeed, the U.S. is a firm promoter of the idea that Huawei 5G equipment, systems products, and services are sensitive to “backdoor” vulnerabilities. From the recent Mobile World Congress (MWC) in Barcelona and official and unofficial communications, to global government- and public statements, the U.S. has been trying to convince as many countries as possible to ban Huawei’s 5G systems outright. This strategy has come with mixed success, as can be seen in various countries’ responses presented in a later section of this article.

Flaws in the U.S.’s Counter-strategy

In some ways, now that there are potentially serious socioeconomic consequences to ignoring Chinese alternative technologies, we see that even European countries are acting with greater neutrality than before. This means that rather than there being a united Western fight against China’s advancement, many western countries are aiming for more balanced approaches between China’s offerings and the U.S.’s calls for bans.

It is also interesting to note that the U.S. has not fully pursued its typical international regulatory tactics in shutting down Huawei or China, especially in light of China’s association with cyber-espionage. Indeed, the Chinese government and many firms within the country have been linked to a number of large-scale cyber-espionage and cyber-warfare cases. Based on history, we would expect the U.S. to be far more heavy-handed in its calls for bans, as it has been in other cases. Yet, we must remember that the U.S. has also been found guilty of the same behavior, including some very rare but high-profile revelations of likely industrial espionage against European companies. For example, the Snowden revelations of “backdoors” in U.S. companies’ software/hardware have been conveniently ignored in most U.S.-led discussions related to China and 5G technology. It could be suggested, then, that the U.S. has not enforced such stringent demands for international regulatory frameworks as, should such changes occur, they, along with China and Russia, may be found to be the greatest offenders of cyber-espionage. It is, therefore, highly unlikely that the U.S. would wish to push too hard for frameworks that may prove their own undoing.

Another point is that the U.S. doesn’t seem to take the “backdoor” question too seriously in terms of its own internal national cybersecurity recommendations for 5G. For example, the aforementioned Secure 5G: The Eisenhower National Highway System for the Information Age report makes no mention of “backdoors”. The report does accuse China and Huawei of using distorted pricing, preferential financing, diplomatic support, suspected payments to local officials, and other means to dominate the global market for telecommunications infrastructure, but it does not mention surveillance, espionage, or sabotage potential. Either this is because the U.S. is firm in its belief that its top-class intelligence services and companies can recognize the “backdoors”, or it does not believe Huawei would risk incriminating itself by compromising its technology in this way. Whatever the reason, it does mean that, perhaps, this whole “backdoor” issue is more of a red-herring that the U.S. is utilizing to turn what is essentially a geopolitical issue with Huawei’s 5G into a legitimate commercial reason for promoting mercantilist economic policies regarding this critical technology.

How Real Is the “Backdoor” Risk?

The concern of “backdoors” that can compromise, or be used to compromise, 5G safety and security has already been highlighted as one of the main areas that detractors voice in this politically-charged debate. It has also been asserted that it might not be as great a risk as some wish us to believe.

In order to discuss the potential “backdoor” risk, let’s look at what Huawei as the lead vendor can do in order to create/hide vulnerabilities in their 5G equipment. Due to the critical role the 5G base station plays in 5G functionality, this station is the key equipment piece that might be compromised by Huawei. The security vulnerabilities could be potentially hidden in the physical components like the electrical semiconductors of the circuit boards, or within the software that configures, manages and communicates the operations of the system. Theoretically, any of these subsystems could contain “backdoors”.

What is less theoretical is the fact that Huawei has been under intense scrutiny for quite a few years by Western intelligence and security agencies. So far, there have been no findings of “backdoors” in the company’s 5G technology. For example, the U.K.’s Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre (HCSEC), chaired by the U.K.’s National Cybersecurity Centre (NCSC), has, in eight years, yet to find any evidence of “backdoors” within Huawei’s 5G tech. However, the HCSEC has found, and given recommendations regarding, issues in engineering practices at Huawei that do not fulfill international best practice recommendations, and which might be causes for security issues in and of themselves.

5G Vulnerability Related to AI

Another potential vulnerability or “backdoor” risk in 5G is its integration of AI systems. 5G networks are much more complex than past network systems, such as 4G, and require the use of AI to manage them effectively. As a result, should AIs associated with the management of 5G fail, or be sabotaged, it could leave entire 5G networks vulnerable.

The reasons for the technology’s complexity are that, firstly, 5G radio technology is much more variable due to more complex antenna configurations and more complicated connectivity means, such as beamforming. Secondly, whilst previous systems focused solely on high-quality voice and data experiences, 5G supports many more and varied use-cases including ultra-low latency and machine communications. These use-cases all have different requirements to each other. Thirdly, 5G networks need to be more dynamic and require additional network resources to scale up or down in real time on an individual level. Thus, at least in theory, 5G performance will be able to vary depending on location, device, time, application, and other factors.

Given these exacting requirements of 5G systems, they will invariably need to utilize AI systems in order to manage their complexities effectively. Simple models can no longer fulfill these requirements. The principal concerns with such AI utilization are:

- How AIs will deal with inputs in extreme cases;

- Their consistency; and

- The typical “black box” concern of not being able to fully and transparently see the reasoning for the AIs’ processes.

This last concern, related to AI transparency, is of particular importance, as a lack of transparency could mean that hidden “backdoors” are created or exposed without anyone knowing or being able to counteract them timeously. However, for such “backdoors” to come about would be extremely complicated. It should be noted, though, that machine-learning AIs are still a new field of technology and it is difficult to ascertain the risks accurately at this stage.

5G Complexity, General Vulnerability, and “Backdoors”

5G systems are, and will continue to be (at least for the foreseeable future), invariably complex and expensive. On the one hand, their benefits are vast, and countries will want to set them up as soon as possible. On the other hand, due to their complexity and the varied uses of these network systems, this also means that 5G will inevitably have many vulnerable areas. In fact, the “backdoors” that could be placed into these systems by vendors is, relatively speaking, only a tiny component of the overall risks and vulnerabilities associated with these complex technological platforms.

In a complex technological ecosystem, such as 5G, subversive hardware or software, i.e. “backdoors”, could be introduced by anyone at any time. Prudent approach would simply accept that such possibility exists and deal with it as with any other security vulnerability. 5G technologies, regardless of the risk of potential Huawei “backdoors”, need to be secured. Implying that somehow without Huawei in the mix 5G would be more secure is dangerously misleading.

Consequence of Bifurcating the 5G Market Because of 5G Geopolitics

From the information presented so far, it is clear that China is the forerunner in 5G development, but that the U.S. and its allies hold potentially viable concerns related to its encroachment. Countries wishing to benefit from 5G will face tough choices as to which camp to adopt. It is also likely that the U.S. and its allies will apply pressure to governments at this decision-making juncture to not rely upon China for 5G.

How might China respond to such pressure? Developing countries that lack infrastructure and financing options (such as many of those currently taking part in China’s BRI) may find the Chinese offer too hard to resist. If China can assemble its own application ecosystem, its offering, particularly to developing countries, will become a “solution sale” as opposed to the more traditional supply agreement presented by the U.S./non-China camp. With this kind of strategy, the Chinese 5G suppliers could hold the ability to implement 5G in all corners of the developing world and disadvantage U.S.-led efforts.

With two major 5G camps, there are several possible outcomes that might impact 5G market adoption and scale over time. For example:

- There might be a fragmenting of the 5G ecosystem into two spheres of influence, namely the U.S. and China. Such fragmentation could lead to further deployment delays and could complicate the ability for the 5G supply chain to achieve its full commercial manufacturing scale;

- A 5G network free of Chinese influence is possible; however, such a network will likely prolong deployment in some countries as multi-sourcing in the supply chain will. be marginalized. This could have the further side-effect of increasing China’s 5G first-mover deployment advantage;

- Interoperability issues could arise between China and non-China suppliers.

- Devices may not have operator certifications to operate on networks outside their supply chain;

- Interoperability issues are already common in 4G deployments due to typically, country-specific spectrum band guidelines. Using industry-ratified standards for 5G can be expected to reduce this risk. Reaching those agreements, however, might become a challenge with a split market;

- Introducing non-standard requirements, such as country-specific security protocols for devices, would be the exception to industry standards conformance.

With such concerns at play, it will be necessary for countries to deliberately and thoughtfully consider all their options.

Countries Weighing in on the China/Huawei Debate and the Geopolitics of 5G

Currently, Australia, New Zealand, and the U.S. have all banned Huawei 5G infrastructure from domestic mobile network deployment options. Australia has also extended the 5G ban to include China’s ZTE.

Canada, a strong U.S. ally and member of the Five Eyes intelligence alliance, continues to test Huawei’s products to understand the security risks the company’s technology might pose.

Germany is tightening its security rules rather than outright banning any 5G supplier. According to the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, who spoke at a March 2019 conference in Berlin, “[Germany’s] approach is not to simply exclude one company or one actor, but rather we have requirements of the competitors for this 5G technology.” In line with this approach, a spectrum auction for 5G is underway in the country, with both mobile operators and industries, such as carmakers, expecting faster data speeds for new applications and services.

In 2018, the U.K. service provider, BT, removed Huawei’s equipment from the core of its EE 4G networks. In March 2019, U.K. government’s Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre (HCSEC) Oversight Board published its fifth annual report. The report doesn’t offer any evidence of Huawei gear having backdoors that would allow Chinese government to spy or disrupt communications, but it does raise a number of concerns about Huawei’s cybersecurity practices that could lead to its gear being exploited by any malicious actor.

While these are some of the prime Western responses to China’s 5G, it will be interesting to see how other countries approach the 5G debate, and into which camp the majority will land. For now, the politicization of 5G is still a real issue, and unlikely to be settled in the near future.

The Bottom Line on Geopolitics of 5G

Some say that it is never a good idea to mix business and politics. Business operates through the lens of metrics and quantitative analysis. Politics is led by emotion, pride in a country, and qualitative elements.

Through the business lens, and particularly within technology markets, measurements of success include time-to-market, delivering better customer value, and distinct competitive advantage. If one company deploys a product or service first, its business plan may include an estimate of how long it will take for competitors to close the gap.

The roll out of 5G is already underway and Huawei has a clear time-to-market lead for infrastructure equipment and software when compared to competitors like Ericsson and Nokia. The question to be asked, then, should be associated with how long it will take to close the current time-to-market gap, and what agreements are likely to be lost during this timeframe.

Through the political lens, economic protectionism is a viable policy. By creating fear, uncertainty, and doubt, some governments hope to appeal to human nature. In such cases as the 5G debate, when faced with a decision and an unclear path forward, it is acceptable to delay decision-making. This strategy may be an effective way to close the gap related to implementation, but it can also negatively impact innovation, the workforce, and other values. As established earlier, the socioeconomic advantages that 5G could bring to the world are massive and delaying its onset could hold dire consequences for countries that fail to keep up with the changing tide.

It is vital, therefore, that national security concerns about China are addressed timeously – either by banning every component manufactured in China by any supplier, or through implementing smarter efforts in testing, monitoring, and hardening of 5G communications and cyber-physical systems connected through 5G networks.

If 5G really starts delivering on its promise of driving the 4th Industrial Revolution, every government and every industry should be worried about being left behind. They should therefore, learn how to respond to competitive threats and cultivate innovation, and to create long-lasting value. Let the geopolitics surrounding 5G be that lesson.

Mobile World Congress 2019 (MWC19): The Latest from Barcelona Related to Geopolitics of 5G

In line with the ongoing and growing division between U.S.-led calls for opposing actions to China and China’s continued growth in the 5G realm, the MWC19 saw its fair share of opposing views.

The U.S. administration sent a large delegation of senior officials from the State, Defense, and Commerce Departments, as well as the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, to make its case against Huawei at the Congress. Conversely, Huawei, a main sponsor of the annual Barcelona trade fair, used its keynote presentation and executive presence to voice its position on the matter.

Asked about Washington’s campaign during a MWC roundtable with media on Sunday, Huawei’s rotating chairman, Guo Ping, said he “…still can’t understand why such a national power wants to attack a company with advanced technologies.”

“We have never and we are not and we will never allow backdoors in our equipment and we will never allow anyone from any country to do that in our equipment.”

“Huawei needs to abide by Chinese laws and also by the laws outside China if we operate in those countries. Huawei will never, and dare not, and cannot violate any rules and regulations in the countries where we operate.”

Guo further noted that technical experts, not politicians, should decide 5G security standards, and that Huawei hoped each country would decide based on “…national interests (and) not just listen to someone else’s order”.

Marin Ivezic

For over 30 years, Marin Ivezic has been protecting critical infrastructure and financial services against cyber, financial crime and regulatory risks posed by complex and emerging technologies.

He held multiple interim CISO and technology leadership roles in Global 2000 companies.